EUSTIS, NEBRASKA — Lane Kugler has forgiven his son-in-law for stabbing to death his only daughter. He holds no grudge for the killing of his two teenage grandsons. He speaks compassionately about the 42-year-old who, after killing his family, turned the knife on himself.Â

But for the mental health system in Nebraska and the rest of the country, Kugler has nothing but contempt.  Â

The Koch and Kugler family poses for a Christmas photo outside their home near Johnson Lake southeast of Cozad, Nebraska on Dec. 24, 2024. Sitting are Peggy and Lane Kugler. Standing from left are Asher Koch, Jeremy Koch, Bailey Koch and Hudson Koch.Â

Until last August, Jeremy Koch was a doting husband, father and son-in-law. Married to Kugler's daughter Bailey, Koch helped build a great room overlooking a reservoir just west of Johnson Lake, about 15 miles southeast of Cozad, Nebraska, for his father-in-law and mother-in-law, Lane and Peggy Kugler. The Kuglers shared their home with their daughter, son-in-law and grandsons, Hudson and Asher Koch.

Koch helped his older son, Hudson, discover and refine his hobby of making bonsai — a Japanese art form that consists of growing and shaping miniature trees inside containers — making the 3½-hour drive with Hudson to Nebraska Bonsai Association events in Omaha every year. Jeremy enjoyed riding jet skis with Asher, especially along the area’s many waterways.

People are also reading…

Koch turned his love for nature into a family business with Natural Escapes, a landscaping and greenhouse business in Cozad. Koch’s sister, Jacqui Hendrickson, said the family sold everything from annual and perennial flowers to soil and fertilizer. The Kochs curated the inventory and property in a way that made it look like “you weren’t even in a small town in Nebraska anymore,” Hendrickson said.

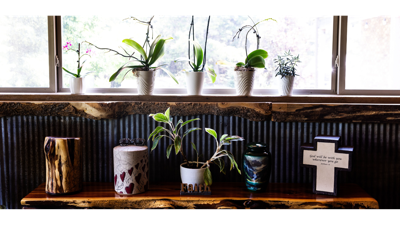

Lane Kugler kept the first bonsai tree that his grandson Hudson Koch grew in his home near Cozad.

“It was like you were transported somewhere else,” she said. “It was beautiful out there.”

For seven years, the Kochs appeared to have lived a happy life. Business was going well. Jeremy, who had attempted suicide multiple times since being diagnosed with bipolar disorder and depression around 2009, was finally on the right combination of medications that gave him peace. Koch’s diagnosis confirmed that he was among the more 20% of the population in the country that suffer from a mental illness.

“Jeremy was absolutely dark-thought free for seven years. He just did wonderful,” Lane Kugler said.

That changed around August last year. The medications stopped working. A hailstorm significantly damaged Natural Escapes, adding strain to Koch’s mental psyche, Hendrickson said.

Kugler said Koch became deceitful, financially irresponsible — which led Bailey to taking away his credit cards — and sometimes unable to get out of bed.Â

On May 10, when he killed 41-year-old Bailey, 18-year-old Hudson, 16-year-old Asher and then himself. All four were found with fatal knife wounds. A knife was found at the scene.Â

For Kugler, it wasn't the many doctors and clinics who failed his son-in-law, and his family. They did the best they could. The problem, he explained to The World-Herald in an interview in the home where he discovered an unimaginable scene, is a national culture of indifference toward the mentally ill. Resources are scarce for the millions quietly struggling and research for treatments are woefully underfunded.Â

The tragedy that befell his family is destined to strike other families, he said. Something must be done.Â

"I absolutely truly believe if we concentrated on mental health, that crime would drop significantly. People do not have anywhere to go," Kugler said.

Enduring challenges

On July 24, 2004, Jeremy Koch and Bailey Kugler, who were high school sweethearts, got married.

A photo of Bailey and Jeremy Koch sit on a chair in the home of Lane Kugler near Cozad.

Lane Kugler fondly recalls their wedding day, which ended with a reception featuring a live band at the home he and his wife would eventually share with Bailey, Jeremy and the two boys.

“Oh my gosh, people had so much fun,” Kugler said, smiling. “We danced and, oh boy, we had a great time.”

Within the first five years of marriage, the couple had given birth to Hudson and Asher. They started Natural Escapes. Bailey Koch pursued and eventually earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education, working for Gothenburg Public Schools and North Platte High School during that time. Koch would eventually earn a doctorate degree in special education from Walden University in 2019.Â

Hendrickson estimated her brother began exhibiting serious mental health issues around 2009. Jeremy Koch's most alarming suicide attempt came in 2011 when he drove head-on into an oncoming semitrailer truck. Kugler called it “a miracle” that Koch survived.

The crash left Koch suffering from internal injuries, Hendrickson said, some of which lingered for the rest of his life. In December 2024, a small bowel obstruction forced Koch to be hospitalized for a couple of days just before Christmas. Although he was discharged just before the holiday, his stay cast a pall over a day he loved.

A former cross country and track runner in college, Koch tried to get back to running and exercising to combat his mental health issues. That led to shin splints and stress fractures.

“I feel like, in more ways than one, his body just wasn’t cooperating with the things he was trying to do to help himself,” Hendrickson said.Â

In the years leading up to their deaths, as Jeremy was prescribed different combinations of medications and treatments, Bailey Koch shared the couple’s frustrated efforts on their Facebook page, "Anchoring Hope for Mental Health."

She documented hospital visits, new treatments, and days where Jeremy struggled with suicidal thoughts. Some posts were hopeful. Others described an urgent desperation of a loved one losing touch. Throughout, Bailey Koch always sought to maintain a positive attitude — a steadying presence for her fragile family. Koch also inspired others — some of whom also struggled or have loved ones who struggle with mental health issues — across the globe.

Kugler said he continues to hear from people who credited his daughter for having saved their lives or the lives of a loved one.

"There are so many people who have gone through similar things," he said. "There's a lot of people out there who need more help."

Bailey Koch said in a post the couple tried electroconvulsive therapy. Jeremy was scheduled to have 17 sessions but they went so poorly the couple abandoned it after only eight sessions. Although Jeremy barely remembered those experiences, Bailey wrote, he had physical responses akin to post-traumatic stress disorder whenever they drove past the hospital in Kearney afterward.

Dr. Kimberly Clawson, an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha and program director for the university’s forensic psychiatry fellowship program, said although electroconvulsive therapy is backed “by a lot of good evidence” to support its use for treating mood disorders including severe depression, there can be side effects that require treatment to be halted.

In her penultimate post on May 8, Bailey Koch expressed hope her husband would be able to begin transcranial magnetic stimulation “soon.”

According to , transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive procedure "that uses magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain to improve symptoms of major depression.” The clinic added transcranial magnetic stimulation is usually used “only when other depression treatments haven't been effective.”

Two days after Bailey wrote that hopeful post, she, her sons and her husband would be dead.

'It’s bad everywhere'

Two days after he found the bodies of his daughter, grandsons and son-in-law, Lane Kugler said anger gripped him.

Lane Kugler talks about the deaths of his daughter and grandchildren in his home near Cozad.

He wasn't angry at Jeremy. Or the doctors who tried to help. Kugler said he was angry at the state of mental health care in the United States, calling the situation “a catastrophe” and “broken” and only getting worse.

Kugler said it doesn’t matter where a person lives — urban or rural — mental health service providers are failing to deliver effective treatments for so many suffering like Jeremy did.

“It’s bad everywhere,” he said. “We have so little resources. … So many people have had horrible experiences because (doctors) guess. There’s no research available to help doctors decide what will be the best one out of those dozens of medications.”

Some parts of Kugler’s opinion were corroborated by Nebraska medical experts who spoke with The World-Herald.

Clawson said there are “a lot” of barriers for people to get mental health access. Those include the lack of qualified behavioral health specialists, patients’ access to specialty care and proximity to relevant providers. Clawson differed from Kugler’s opinion in saying those living in rural areas have a harder time accessing mental health resources than their urban counterparts.

“Those are problems that are all exacerbated when you live in a rural area and don’t have a lot of options when it comes to providers,” she said.

The Behavioral Health Education Center of Nebraska, which is based at UNMC, has been working to address that gap. The center, which was established by the Nebraska Legislature in 2009, has tracked the mental health needs of all of the state’s counties and have developed workforce behavioral health models to address the mental health needs of a region’s population, said Dr. Marley Doyle, the center’s director.

“We quickly realized the behavioral health needs across communities were vastly different,” Doyle said.

The golf clubs belonging to Hudson, left, and Asher Koch, in front of a photo of them in the home of their grandfather Lane Kugler near Cozad.

Since the center started tracking the state’s behavioral health workforce in 2010, that workforce has increased by 44%, Doyle said. The center has six sites across Nebraska, operating in what Doyle called a “hub-and-spoke model” where site directors work with local behavioral health providers and find out what’s going on in their respective regions.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic and especially over the past year, Doyle said providers, particularly those who specialize in outpatient care, have reported an increased demand for mental health services and cases are getting more severe.

When a patient has a more severe mental health condition, Doyle said: “You have to do a lot more to kind of get this person back to their previous level of functioning.”

Doyle added outpatient providers are now providing care that used to be done in settings where a person would stay in a hospital for at least one night.

“That creates stress on the system because that level of care isn’t necessarily equipped to meet their needs. It kind of creates this bottleneck,” Doyle said.

Doyle said center officials and behavioral health professionals who were shocked by the Koch family's horrific tragedy, convened in the region, asking themselves what can be done to prevent future tragic events. Â

Some steps taken included hosting listening sessions in North Platte and Kearney and holding targeted crisis response trainings in the southwest and south-central regions of Nebraska. Doyle said behavioral health center officials will continue to work with regional behavioral health care providers to develop interventions.

“We very strongly believe that you can’t just do a one-time thing,” Doyle said. “We don’t yet know fully what needs might come from this. We’re just kind of starting. I’m sure there are other things we will do as we hear feedback.”

Kugler said he has not yet heard from the Behavioral Health Education Center of Nebraska or other behavioral health professionals since the killings.Â

'We need to invest in mental health care'

Bailey Koch, through her openness and advocacy for better mental health resources, had been a source of comfort and inspiration for many people going through similar struggles.

Since her death, many people have reached out to Lane Kugler, who has vowed to continue his daughter’s mission of providing hope to people who have mental health issues or know someone who does.

Kugler believes his daughter’s advocacy “struck so many people deeply that they reached out.”

“They’re still reaching out,” Kugler said. “They understand that we need change. I feel that is because they all have children, they have grandchildren and they could not imagine what it would be like to lose like what we lost. It’s just beyond comprehension for them.”

A sticker on a car for Anchoring Hope for Mental Health at the home of Lane Kugler near Cozad.

Kugler said he has pushed for change in part by writing letters to all five members of Nebraska’s Republican congressional delegation as well as Gov. Jim Pillen in early June.

With Kugler’s permission, The World-Herald followed up with the offices of these elected officials. U.S. Sen. Deb Fischer and U.S. Rep. Adrian Smith, whose district covers where Bailey, Jeremy and their sons lived, responded with statements expressing condolences and urges to increase access to mental health treatments.

“My heart was shattered when I heard the tragic news about the Koch family, and I’m continuing to pray for their loved ones during this very difficult time,” Fischer said. “It is important we all work together — as family members, friends, and neighbors — to do everything we can to make sure folks receive the assistance they need so we can help prevent unspeakable tragedies like this from occurring.”

Smith said: “An unspeakable tragedy like the one suffered by the Koch family brings attention to mental health issues which are a particular challenge in rural areas. Regions like many in Nebraska’s Third District lack providers, so greater flexibility is needed to improve access to mental health care.”

A spokesperson for U.S. Rep. Don Bacon noted the congressman, whose district covers the Omaha area, is chair of the GOP Mental Health Caucus and has lost a brother to suicide and two brothers to drugs. Bacon’s three brothers, the spokesperson said, struggled with mental health issues.

Spokespeople for Fischer, Smith and Bacon pointed to legislation each of them has introduced.

The Kugler and Koch families celebrate Bailey Koch's graduation from Walden University in 2019. From left are Peggy Kugler, Hudson Koch, Bailey Koch, Lane Kugler, Asher Koch, Jeremy Koch and Jeremy's mother Pam Koch.

In late May, Fischer, along with Democratic U.S. Sen. Tina Smith from Minnesota, reintroduced a bill that, if enacted, would create an online dashboard to help applicants in identifying federal grants that support mental health and address substance use. The two senators first put forward the bill in 2023.

Fischer’s spokesperson also said the senator helped secure $2.5 billion for research efforts at the National Institute of Mental Health. The spokesperson added Fischer also supported legislation to establish a mental health crisis hotline.

Smith’s spokesperson said the representative introduced a bipartisan bill in 2023 that, according to the Nebraska Rural Health Association, would bolster mental health efforts across the country. The spokesperson also said Smith introduced legislation in 2021 that was folded into a 2023 congressional appropriations bill that expanded access to peer support specialists trained to support those who struggle with mental health, psychological trauma or substance use.

Bacon’s spokesperson said the representative introduced bipartisan legislation in late June that would address ongoing mental health needs in public education, which have increased in recent years because of the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread teacher shortages, difficult working conditions, and student behavior issues.

In early May, Bacon was a co-sponsor of legislation that would address mental health treatment shortages. The legislation, if passed, would establish a new loan and loan guarantee program within the Department of Health and Human Services to build or renovate mental health or substance use disorder treatment facilities and reserve at least 25% of the funding for pediatric- and adolescent-serving facilities. It would prioritize facilities in high need, underserved or rural areas.

U.S. Sen. Pete Ricketts’ and U.S. Rep. Mike Flood’s offices did not return requests for comment. A Pillen spokesperson declined to comment.

United in tragedy

In the weeks after the tragedy, the surviving Kuglers and Kochs have found a source of comfort in each other.Â

“The Koch and Kugler families have been together for more than 20 years,” Hendrickson said. “This isn’t going to change that. We’re still family and the four of them tied us all together. It would just be so hard if we didn’t have that connection.”

Lane Kugler touches one of four urns on a table in his home. They contain the remains Jeremy Koch, his wife, Bailey, and his sons, Hudson, and Asher.Â

On a table on one side of the great room in Kugler’s house sit four urns that contain the ashes of Bailey, Jeremy, Hudson and Asher. Bailey’s glasses are resting on top of her urn. Hanging high nearby are their individual portraits, each one with smiling faces.

Kugler acknowledges keeping Jeremy Koch’s picture in such a prominent place might seem unusual — a constant, visible reminder of the person behind such a hurtful act. But to the Kuglers, Koch is still a cherished family member who could no longer control his dark thoughts and actions.

“A lot of people don’t understand how in the world I can possibly forgive Jeremy,” Kugler said. “That wasn’t Jeremy that did that. It was a very, very sick mind that couldn’t stop the sickness.”